Buying skis (or indeed any ski equipment) can be a daunting experience, and is a topic we are often asked about. No wonder: these are incredibly technical pieces of equipment, and you can’t be blamed if you don’t know the first thing about a manufacturer’s ‘brand new vibration performance system’. It’s not as if they explain it to you either; they just tell you how great it is. Anyway, fear not, for help is at hand.

The three key elements that are going to majorly affect your ride are width dimensions, length, and stiffness.

Width dimensions

You’ll often hear terms like ‘radius’ and ‘sidecut’ thrown around, and it’s easy to be confused.

All modern skis have a set of dimensions; three numbers that determine their width. For instance, 122-86-115. This means they have a width of 122mm towards the tip (the widest point), a waist width of 86mm (under the foot), and a tail width of 115mm.

The dimensions of a retail ski are often printed towards the back, although with the number of artistically-designed freestyle models available, this is not always the case. If that fails, any shop assistant or manufacturer’s brochure/website will be able to inform you.

That’s all very well, I’m sure you agree, but how are width dimensions important? Well, they decide two things: the radius, and the average width.

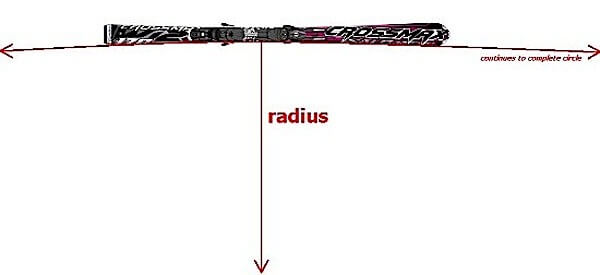

The radius measurement, measured in metres, is the radius of the circle that would be drawn if you were to extend the edge indefinitely outwards (see picture below). It is effectively the turning circle, and is suggestive of how long it will take the ski to complete the tightest turn possible.

To give you a rough idea of the figures involved, slalom skis – designed for the quick and short turns of slalom courses – have a correspondingly short radius (FIS regulation is 13m for men). This moves up through giant slalom skis (FIS regulation is 27m), super G skis (FIS regulation is 33m) and downhill skis (FIS regulation 45m). Typically, ‘cross’ skis and other retail models designed for on-piste performance will have a radius somewhere between a slalom and giant slalom model, whilst other freeride boards get bigger and bigger the more they are geared towards powder and off-piste.

It’s clear from those numbers that skis which are regularly required to perform tight turns will need a shorter radius. This isn’t to say that your big powder ski just can’t do short turns – a good skier will always be able to slide a turn on a ten pence piece – but carving them cleanly will be beyond its capabilities.

So why don’t all skis just have a short radius then? Because, as with all things in ski technology, there is a trade-off. The trade-off here is that a ski with a shorter radius will have to be narrower underfoot to create a larger difference in waist width and tip/tail width (a bigger shape, or ‘sidecut’). If narrower underfoot, the average width will also be narrower, and this is not always beneficial.

First, it takes longer to transfer a wider ski from one edge to the other. For performance in short turns on hard pack, a ski that is comparatively narrow will be quicker from edge to edge, and this will allow you to engage into the next turn more quickly, and carve sharper turns. In slalom racing – a sport where fractions of a second matter – having skis that respond quickly to changes in direction is particularly important.

Second, a ski with a narrow average width will have a smaller surface area on the snow. A greater width (and therefore surface area) is often used for freeride because it allows the ski to stay on top of deep snow rather than sink into it, and this allows the rider to float on the surface of the snow, maintaining manoeuvrability and momentum (the last thing you want on a flatter section of your powder run is too sink into heavy snow and grind to a halt). This is why powder skis typically have a bigger radius than piste and race skis – because they need the extra width to stay on top of deep snow.

To recap on width dimensions:

1. A big difference in tip/tail width and waist width creates a short radius, which allows you to carve tight turns.

2. A ski with a short radius will also be a narrow ski.

3. A narrow ski will transfer from one edge to the other more quickly than a wide ski, and will feel more responsive on the piste.

4. A wide ski will have a larger surface area on snow than a narrow ski, and won’t sink into deep snow as quickly, increasing manoeuvrability and momentum.

5. A slalom ski is needed for short, quickly-linked carve turns on piste, which explains why it is narrow with a radius of about 13m.

6. A big mountain powder ski is needed for big, open turns in deep snow, which explains why it is very wide with a radius that can exceed 45m.

Length

With width explained, length is relatively simple. Longer length, like width, increases the surface area of the ski on snow. This has, firstly, a similar effect to having a wide ski – greater floatation in deep snow, which is why you’d think twice about going heli-skiing on 165cm, the regular length on a slalom course. A second, linked effect is that with more surface area on the hill, your weight is more dispersed (i.e. less weight per square metre), and so friction between base and snow will be decreased. With less friction, you will accelerate more quickly and to a faster top speed down the hill.

So why don’t slalom specialists ski on narrow, short-radius yet long skis? The trade-off on this occasion is that as you increase the length of a ski but maintain the same width dimensions, the radius will increase (the difference in tip/tail and waist width is the same but spread over a longer distance, so the sidecut will be less), and this will stop the ski from carving turns as tightly. Simply, a longer ski will give greater straight-line acceleration and maximum speed, but will enlarge the turning circle.

That’s why speed skiers and ski jumpers wear skis that on occasion approach 250cm (no turning required, just straight-lining), downhillers use ones of around 215cm (some turning required, still lots of straight-lining), and slalom skiers tear through the gates on about 165cm (lots of turning required, little straight-lining).

1. A long ski will have a larger surface area on snow than an identical, shorter ski.

2. A ski with a large surface area will not sink into deep snow as quickly as a ski with a small surface area, increasing manoeuvrability and momentum.

3. A ski with a large surface area will create less friction on the snow, increasing its acceleration and maximum speed.

4. A long ski will have a large radius, and will not be able to turn as tightly as a short ski.

5. A slalom ski is required to perform lots of turns and little straight-lining, which explains why it is short with a length of around 165cm.

6. A downhill ski is required to perform fewer turns and lots of straight-lining, which explains why it is long with a length of around 215cm.

Stiffness

This is an important but easy concept to follow; radius means nothing if you can’t flex the ski.

Put your skis together, and you’ll notice that they only touch at tip and tail, bending away from each other at the waist. This is called camber. The camber exists because a carve is created from the force underfoot pushing the waist of the ski away from himself, into the snow and the outside of the turn. The flexed ski creates a banana shape (a reverse camber) in the snow, and following this shape, the ski travels round in a carved turn. Forget anything you might have heard about reverse camber skis, a new innovation in powder skis.

The amount of pressure you need to apply to a ski to flex it from its normal camber shape into a reverse camber in a turn depends on how stiff it is. A stiffer ski will require greater power to flex it into a reverse camber, and will be less forgiving when travelling over bumps and landing air. This can be a bonus when the pressure being applied by the skier is very large (e.g. through a fast turn in a World Cup giant slalom) for two reasons. Firstly, push a soft ski too hard and it will give in and slide away from you, whilst a stiff ski will hold its edge and continue to track through the turn even when it is pushed very hard. Secondly, a stiffer ski will snap back into its original shape more powerfully as the pressure is released, and this explosiveness can aid acceleration out of the turn.

As a rule, freeride skis are softer, as they need to be more forgiving to absorb bumps and stomp landings in the park and won’t require as much pressure to carve on less stable terrain. Meanwhile, skis designed for on-piste performance (particularly race skis) are stiffer, as the skier presses much harder to push out of his turns and so accelerate out of a carve, and this is all done on a very stable, hard pack race piste, where the snow is unlikely to give way. This also explains why softer powder and park skis don’t perform as well on the piste.

Skis also differ in stiffness according to ability and sex – beginners‘ and women’s skis are softer than high-end models because the person using them tends not to be as strong in the pressure they can apply in the turn. Whilst stiffness isn’t measured like radius and length, stiff skis are aimed at experts and so they reside at the top end of any line of skis that a manufacturer produces.

1. Skis are made with a camber, to allow for carved turns.

2. A reverse camber shape is made in the snow when pressure is applied underfoot by the skier, and this carves the ski in a turn.

3. Soft skis absorb bumps and heavy landings more easily, and require less power to carve.

4. Stiff skis will hold an edge more firmly in a turn when a lot of pressure is applied, and will have greater explosive power to accelerate out of a turn.

5. A slalom ski is required to perform powerful, accelerating turns on a stable piste, which explains why they are stiff.

6. A big mountain powder ski is needed to negotiate bumpy terrain and turn on unstable deep snow, which explains why they are soft.

7. Less capable skiers and female skiers tend to be weaker, and require relatively softer skis.

This explanation has been helpful to me.

One thing about friction between snow and ski: theoretically, the friction force depends only on the coefficient of friction.

For static friction , F=uN where N is the ‘normal’ force, F is the frictional force, u is the coefficient of friction. (more complicated, but similar for dynamic friction)

u is a function of the surface contact between the two surfaces.

This force ‘F’ does not primarily depend on surface area.

I think the change due to greater surface area of skis is more of a geometrical effect rather than purely friction. The ski sits higher and is pushing less snow.

Very interesting, thank you. I am only 14 weeks of holiday into skiing and have a point that might be promoted at this opening. Though I am athletic[ish] like most people I found it frustrating and hard to get good enough to get going at the beginning. Indeed I nearly croaked after seeing a sign at Champoluc saying Peligroso [or similar] forcing my non working snowplough to turn right towards what I was sure was a Peroni bar only to find I shot over a 82 degree cliff. Whatever it said it meant ‘Danger’ in Italian not ‘Nags Head this way’.

I struggled on for a couple more years with 162 planks lashed to my legs, as every purist assured me was necessary, but that thwarted every kinaesthetic effort that I made. Then I bought Salomon 120 and eureka it was like heaven had opened up. I instantly went parallel indeed my tight turns were better than any instructors and remain so [radius 8]. They are wonderful things and allow me to go anywhere on-piste [sure I expect that I would sink pretty quickly off piste but no if I wanted to do that I would buy 125 or 150 Floskis – look them up].

I thought that I was alone in this near Vedic knowledge but on reading up of Les Arc where I am going in January I learnt that they have a ski school that starts people off with short skis for this very reason. Perhaps more should try it and avoid years of coughing up for a snow plough that they will rarely need.

Bon Chance

GEOFF

thanks peter! now I know all the measurement numbers makes sense after reading your indepth article. I have pair of old rossingnol skis and i could not find this pair in their collection. Or I may not looking at the proper numbers on the skis. I see a number 160 6 e 386. I wonder how to identify which year it was made.

Hi Anitha,

That number is the length of the ski. What you need to tell me is the model name of the ski – that might give me an idea of the year of manufacture.

With the stiffness consideration, I think it’s more than just type of skiing – snow conditions usually are the deciding factor for me between my stiffer and softer skis. Softer skis in the sierra cement, stiffer skis if you’re hitting the east coast’s semi-vertical icing rinks.

Peter, I just demoed Blizzard Brahma 180 and Vokl Kendo 177 and coul hardly tell the difference. Definitely less tip vibratioj on Volkl though. I skied at Northstar, CA 2 days after i snowed. Some spots were icy, but most of the runs were nice. Inam an intermediate to expert skier. Wold you recommend one over another or i should try something else. I only want to have 1 pair of skis. Thanks so much.

Peter

This an excellent article.It connects the dots among different variables which are not clear in articles elsewhere. My question is whether stiffness is linearly related to length on the same model ski.I am 1.70m tall, 75 kg athletic and carve complete S turns (rounding them up) on on 156 Heads Supershape.Recently, I tried 153 Heads Super Joys (a woman`s carving ski) at least 1.5 kg lighter than my other skis and the results were impressive.It held an edge even on hard pack and turn initiation was instantaneous. One day I rented a Rossi Hero SL 163 and could not flex it at all when turning although the edges engaged almost instantly.I suspect that only custom ski manufacturers can dial in the stiffness you want and camber to skis.

What do you think?

Thanks