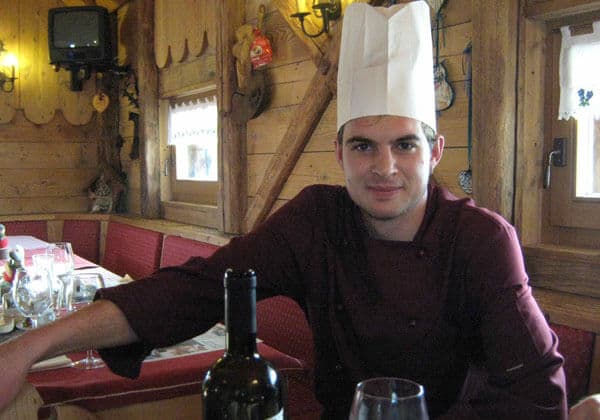

Pictured above is Livio Gabrielli my guide, hard at work in one of the best restaurants in the Alps – Baita Checco. It’s set in the small but stunning ski area of Catinaccio, which lies between the resort towns of Moena and Canazei, in the Val di Fassa. I took the picture just as we were starting a memorable lunch: a slow and mouthwatering progress through some of finest ingredients the region has to offer.

We ate cheese from Campitello, just down the road, salt beef made by the restaurant’s owner (Pierre-Paolo Trottner), local venison salami, a sensational orzotto, which is like risotto but made from barley…

…polenta with sausage and porcini mushrooms…

…veal which had been slow-cooked in the oven for 48 hours…

…more venison…

…and then a trio of deserts…

…all washed down with a very agreeable red from just south of the town of Trento, and made from the local Teroldego grape.

Oh yes, and we finished with grappa, of course.

We ate in a tiny wood-panelled room on the hut’s upper floor, which was home to the bar, five tables, and an ever-changing cast of locals, ski instructors and grinning holidaymakers who couldn’t believe their luck – having stumbled upon the kind of mountain restaurant you always dream of but never expect to find.

Along the way, we marvelled at the prices. Venison tagliatelle costs 8€, spaghetti al ragu (spag bol) 6€, a hot chocolate 2€, and an espresso 1€. Our wine was 15€ a bottle, and the most expensive item on the menu cost 17€.

We also met the chef, Matthias Trottner, who is the nephew of the owner He’s only 22.

“What’s your secret, Matthias?” I asked.

“Keeping it local,” he replied. “I get as many of my ingredients as possible from the valley. That means I know the suppliers personally, and I always get fresh, high-quality produce.”

“Yes, but there must be a lot of hard work involved, too,” I suggested.

“It’s not really work when you’re enjoying yourself,” he replied, and I was suddenly reminded of Boris Becker, winning his first ever Wimbledon back in 1985. Mattthias has something of that insouciance about him – as if it’s still a game for him, and he’s winning all the time.

We were the last to leave, but there was still time to take in a few more laps of the Catinaccio pistes before home time. Which also meant there was more time to stare open-mouthed at the scenery: a great wall of raw Dolomite rock, fractured into a hundred towers and cliffs. I still can’t quite believe I saw it. And I certainly can’t believe that the whole of Pozza di Fassa’s brass band climbed two of these towers to celebrate its 70th birthday, and sat on top, playing a brass-band tune.

When I wasn’t taking pictures, I was hurrying down the slopes in pursuit of Livio. If Elisabetta, my guide on Monday, skis at Mach2, Livio must ski at Mach4. He’s a ski instructor who never had any lessons himself (“I learned by looking,” he says), and is one of the most natural skiers I’ve seen. He barely seems to be skiing at all – a few graceful turns, and then suddenly he’s at the bottom of a black piste travelling at a gazillion miles an hour. It’s not just the control, or the speed, that’s impressive – but the line he takes down each piste. He makes use of every bank and roller to make the descent more interesting. It’s inspiring stuff.

Of course, hardly anyone comes to Cantinaccio, despite the popularity of Canazei, a little further up the valley. In fact, hardly anyone even knows it’s here, apart from the locals. Which is probably just how it should be. That way you don’t have to worry about other skiers as you hurtle down the steep and steady slope of the Tomba black, or wind through fast 90 degree turns down the area’s two sinuous and deeply satisfying valley runs (one of which is about 6km long).

You don’t have pay inflated prices at Baita Checco, either.

So forget I ever told you about it, will you?

Add Comment