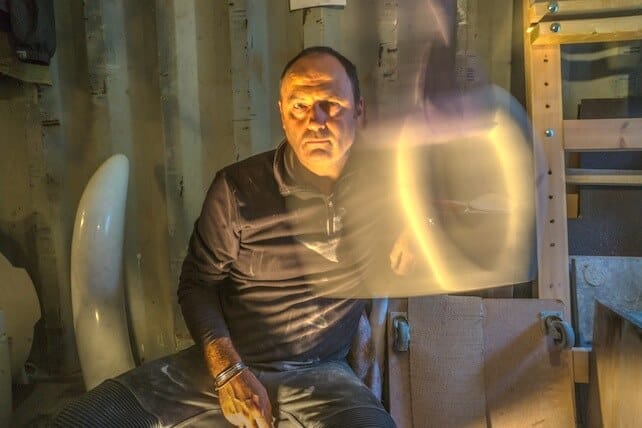

William Carey is a sculptor and an experienced skier who used to ski with the army. In 2010, he was buried by a small but potentially lethal avalanche in the Alps. This is his story.

The following is based on the notes I wrote on scraps of paper a few hours after I was dug out of a north-facing slope to the north of Crevacol in Italy.

By sharing my experience I hope I’ll encourage everyone to ski more safely this winter.

February 26, 2010

I’d been staying in Verbier with my friend Dave (of No. 14 Verbier) and we’d decided to to drive through the Great St Bernard tunnel to ski beautiful Crevacol in Italy with our UIAGM/IFMGA mountain guide. The weather looked perfect: blue sky and no wind. It was quite warm by the time we started, but it seemed fine to ski the north-facing slopes. The avalanche risk level for Verbier was 2 when we left.

We had purchased our day passes for 24€ and bought some water at the cafe at the bottom of the lift. There were two other groups there, one of which also had a mountain guide. At the top of the second chair-lift we put skins on our skis and walked west along the ridge for about 15 minutes. It was very beautiful up there and the snow seemed perfect. All the groups removed their skins at the same place and one headed off in a southerly direction. The other group headed off with their guide before us on the north face.

We took a slightly different route where there were only three tracks. The snow felt fantastic. We came to a ridge and could see some members of the other group about 250m down the slope. We could see that they had apparently set off a small avalanche, which was to the right of where we were heading and on a steeper pitch.

“I noticed a small crack open near one of his top turns”

Our guide decided we should go down a flatter part of the slope where three tracks had been made earlier. He set off first, telling Dave and I to make tracks just to the right of his. I thought he said he was going to ski down to where we had seen the other guys, but in fact he stopped at a natural ridge point about 100m below. This part of the slope was a bit of a bowl funneling in towards the ridge where the guide was waiting. It was a bit steeper than what we had done so far but looked a good slope. I wrote what follows next when we got back to Verbier. It may not be completely accurate in all areas, but it is an account of precisely how things seemed to happen to me at the time.

“After Dave had gone it was my turn. I had noticed a small ‘crack’ open near one of his top turns, and I shouted down to our guide to confirm that he still wanted me to go to the right of his tracks. He said yes. This was the least steep part of the slope and as five people had been down before me it seemed fine to me.

On my second turn I felt the whole part of the slope I was on give way above me and almost immediately another large crack opened up beneath me on the moving slab. I tried to ski straight down and then out of the fall line, but I had no sensation of my skis being on the ground. It just felt like I was falling. I realized that I was not going to be able to stay upright so made a concerted effort to ‘swim’ with my arms in order to keep my head above the snow. This did not work and very quickly the snow swept over me and then continued to build up on top of me. I could tell this because the weight gradually increased.

I had many thoughts almost simultaneously. I could not believe the weight of the snow pressing down on me. I could feel my transceiver pressing into my lower ribs. I was pretty certain that I was face down with my back arched and legs out behind me. There was complete darkness and silence. The snow was pressed up against my face and my helmet and glasses had stayed on. I could not move my legs or my right arm, which was outstretched above my head and ‘handcuffed’ to the snow by the strap of the ski pole. I could feel the panic rising in my chest but at the same time knew I must try to control that. Luckily my left arm had been encased at a 90 degree angle to my body but with the elbow fully bent meaning my left hand was close to my face – like a bad attempt at a military salute but using the wrong arm.

“I couldn’t believe how quickly I had become buried”

Whilst my left arm was restricted by the snow and manacle of the ski pole strap, I was really lucky I could move my left hand which was near my face. I was able to move my fingers and push the snow from my face. This created an air space which I knew was important. It still felt incredibly claustrophobic and basically I was in pitch black. I pushed the snow as hard as I could but this compressed it and made it hard. I then started to wiggle the fingers on my right hand. I could feel that the snow felt a bit less compacted there and after moving the hand and arm a bit some light came in and I knew I had clear air. The light was like being in a bedroom with very heavily lined curtains shut during a grey day. I could move nothing else at all. The weight on my back felt like having a very heavy man sitting on top of me.

When I couldn’t see and the snow was up against my face it was terrifying. I couldn’t believe how quickly I had become buried. I also could not believe how solid the snow was. I had always imagined that in this situation one would be able to force the snow away enough by compressing it and in effect make a cocoon. It was a shock to realize that this was completely wrong. I had to concentrate on not panicking and breathing very calmly. Once I had some light this became much easier. It was at this point I shouted our guide’s name as loud as possible. I shouted three times and was very relieved when I heard him shout back “coming” I think. Afterwards I learned that Dave had not heard me shout once, yet he can have been no more than 50 feet from me and it was a calm day.

For a very brief moment I relaxed. It felt incredibly comforting that to be wearing my Mammut transceiver. It would have been even more lonely without it. However I then realized that all would very much not be okay if more snow came down. My light and air would go. I knew other skiers were out and could follow our tracks so I shouted to our guide to please make sure no-one else skied above me. He had obviously already thought of this and had told Dave to keep an eye on the mountain and shout to anyone who came our way to stop.

“I felt his glove on the back of my helmet”

I did not enjoy the wait with this thought in my mind. I heard the guide digging above me and then felt his glove on the back of my helmet. Very quickly he cleared a space to the left and under my face. There was fine snow, which was easy to breathe in for a moment and then daylight and the claustrophobic feeling went. He then got on with digging me out.

All I had seen of him was his glove. He said he needed to use a shovel and asked me how I was lying. Rather ridiculously I told him I had a shovel in my back pack! I told him it felt like I was lying straight out on my front with my legs outstretched. I did not know where my skis were. He then got on with shoveling the snow off me. I did not care if a shovel hit me! (It didn’t actually). He would ask which bit if my body he was touching as he uncovered me. Obviously you can’t tell from a patch of clothing what part you are looking at.

He told me to yank my right arm, which I did and the pole came free and finally I was able to push myself up on my knees. He then worked to free my right ski which had stayed on. He also said he knew where the left one was, having hit it when working his way up to me. It was a lovely moment to poke my head out of the hole the guide had made, and look down and see Dave! I thanked the guide very much indeed! I think that he too was quite shocked by the whole thing. It was the first time he had ever had to dig someone out in 20 years of working as a mountain guide. He had to work very hard to cover the 25m uphill in deep snow to get to me. Dave said he was initially digging frantically, like a dog, with snow going everywhere as he worked to expose my head.

Dave’s estimate is that I was under the snow for about five minutes before the guide exposed my head. I was probably stuck for another six minutes whilst he dug me free. 24/02/10”

Dave’s estimate is that I was under the snow for about five minutes before the guide exposed my head. I was probably stuck for another six minutes whilst he dug me free. 24/02/10”

I have included the estimates of time because that is what it felt like. However, I was wearing a GPS/heart rate monitor at the time – and the data shows that from being buried and motionless to moving off was just under 12 minutes. Having traversed across the slope about 20m I made one turn before the slide started. The point where I was buried was about 80m below this. From making the first turn to being still took 15 seconds. The guide climbed up between 20 and 30m to get me out.

The reason the snow built up on top of me so quickly – as opposed to carrying me down the mountain – was that we were both funnelled into a hollow. I estimate that the depth of the hole I climbed out of was three foot (91cm) – about up to my hip at its deepest. I don’t think my head was that deeply buried: but all the same I could not move an inch. Looking up at the fracture line in the snow I could seen the slab had been about 6-8 inches (15-25cm) deep. It was subsequently shown our guide was right to tell me to take the track I took because later another guide skied to the left of the same slope, which was steeper, and brought down a larger avalanche

When it was going on I was totally disorientated. I thought I was skiing out to the right of the avalanche – in fact the avalanche had pushed me so I was moving left across the face.

I have to say that our guide handled everything brilliantly. He got me out quickly and got us down the hill, carefully and safely. I was confident that I was in the best possible hands at all times. Thank goodness he was there with us.

Lessons I have learned

• This was a small avalanche or snow slide. Don’t underestimate the power and strength of even a small avalanche. I would not have got out if alone. Even now it seems amazing that I could have been buried on such a slope.

• Bring your hands in front of face before being submerged. If my left hand had been trapped away from my face, like my right, I would have not been able to clear space in front of mouth, nose and eyes. I was very lucky on this point – as it would have been very nasty trying to breath otherwise.

• Take your hands out of the straps of your ski poles when you ski off-piste. My hands were restricted by them once I was buried. (Editor’s note: your poles can also get you into more trouble as the avalanche unfolds. Klaus Kranebitter, Austrian mountain guide, and instructor with SAAC says: ski poles “work as anchors in an avalanche, pulling you down and causing you to be more deeply buried.”)

• Wear an avalanche airbag rucksack. Hire one if you don’t want to buy one. Now, I would always want to have the option of inflating the bags for this type of skiing.

• Pull the ABS toggle as soon as you feel ground moving – even if you think it’s a small avalanche and you’ll be fine. Don’t try to second-guess an avalanche. It could easily get worse. We reckoned only five seconds passed between the start of the avalanche and me going under, so you’ve got to react immediately.

• Always wear your transceiver and make sure it is in good working order with good batteries. Make sure it has been checked to work with all other members of group at the start of the day. I found it very comforting to know mine was working even though our guide knew exactly where I was and they were not needed this time. Every member of the group should also have a shovel, avalanche probe, first aid kit and fully-charged mobile phone, with emergency numbers pre-loaded.

• Never do this type of skiing alone.

• Always ski with a guide. Aside from the obvious benefits of having a trained and experienced group leader, a guide can also make a critical difference in the event of an accident. If I had been skiing alone with Dave alone (who knows the area well), it would have taken him at least five minutes longer to get to me than our guide. That would have felt like a very long time to me. Guides are fit and strong and can cover the ground a lot quicker than mere mortals!

• Ski one at a time, and think carefully about where you stop. If the guide and Dave had gone to the next ridge I would have been buried 130m above them. That would have taken anyone a long time to climb back up.

(Editor’s note: I’d like to add one final point to William’s list – don’t assume that because another group has already skied a slope, it’s safe to make your descent. Changing weather conditions can quickly affect the structure of snow and the safety of a route.)

• Completely unrelated to this we had both become Patrons of Rega Swiss Air Rescue which, for 30CHF offers emergency heli rescue cover in Switzerland and Liechtenstein for a year. Obviously this event happened in Italy but it feels good to have this for Verbier or any other Swiss resort.

Lastly I cannot emphasise enough how innocuous the slope looked. It was not large, it was not very steep, the conditions looked good. Yet the length of time it took between realizing I had a problem and being buried was probably no more than five seconds.

It surprised everyone. It was not a nice experience.

Postscript

I initially wrote down my experience as a way of trying to process it. I then sent it to some friends who were interested in what had happened and my guide asked if he could use it for the Mountain Rescue courses he teaches in Sweden. I remember at one point feeling a little uncomfortable – was I being melodramatic? But the fact I never edited or post-rationalised my account, written within three or four hours, meant that I was comfortable that the feelings I recorded were true at that moment.

Within a matter of weeks two events removed any feelings of doubt about how serious my incident could have been. First a friend of a friend who had read my account was killed. The similarity was that there were two skiers with a guide, and it was the first time the guide had been involved in an avalanche accident 25 years. Secondly there was a separate incident when someone lost their life in a small slide. Their head was only covered by 12 inches of snow when found.

“I could feel my body trembling, but on the inside”

There were some surprising after-effects. For several days when lying in bed at night very quietly I could feel my body trembling, but on the inside while outwardly I was still. My senses were noticeably heightened – especially my hearing – I remember at the time listening to some classical music and it was almost like I could hear each component part of the orchestra. My head felt very clear and it definitely helped put what was important in life into perspective. It was almost like I had had my hard drive cleaned and been rebooted! Unfortunately it only took a few weeks for things to start to get cluttered again.

I was also aware how much more frightening this could have been for a child or young teenager. I don’t know how or why, but I recognised the importance of not panicking almost immediately, so after the initial wave of fear had risen up I realised that could be the most dangerous thing of all when trapped. Having shouted at the top of my voice initially I then really focused on keeping my breathing as slow as possible. This worked and the HR monitor shows my heart rate dropping as a result. Also I was using less oxygen by doing this.

I think that preparation and fitness are really important. Complacency is not a good companion when doing this type of sport and if others are relying on you to decide where to go you need to consider these two aspects.

Editor’s note: also see our features on top off piste tips, ski safety and Avalanche Airbag Rucksacks.

Off-pisters should also consider attending an avalanche awareness course, such as those offered HAT in Val d’Isere and Tignes, and SAAC in Austria, so that they can develop their own understanding of the risks, even if they’re skiing with a guide. Anyone who’s developing an interest in the backcountry should also read Bruce Tremper’s Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain – a detailed guide to evaluating avalanche risk, which at the very least will teach you how little you know about snow.

To discuss his experiences further, you can email William Carey here.

Avalanche: a survivor remembers. https://t.co/2IaB5Kb9wq

Some excellent lessons shared in this article! RT @welove2ski: Avalanche: a survivor remembers. https://t.co/z9DtuZtW1I

Thank you Henry, your comment is much appreciated.

Bu kış #Kayak yapacaklara önemli bir uyarı… Avalanche: a Survivor’s Guide | Welove2ski https://t.co/VZTLuGOW1Z

A great Survivor’s Guide to avalanches via @welove2ski | #ski https://t.co/DxmRnfJOwc

Worth a read by all off-piste skiers. https://t.co/fKBFsRCat8

One #skier reflects on a recent avalanche experience to educate others about avalanche safety. https://t.co/2PNEHDMSGo

I can’t believe this man got stuck in an avalanche! Use his tips to ski more safely this winter: https://t.co/xTWFSsQ1WV