Why does this matter to skiers? Because El Niño is part of a two-sided climate anomaly generated in the Pacific which sometimes – but not always – has a dramatic effect on snowfall in North America.

Here’s a great video explanation from the UK’s Met Office about how it forms.

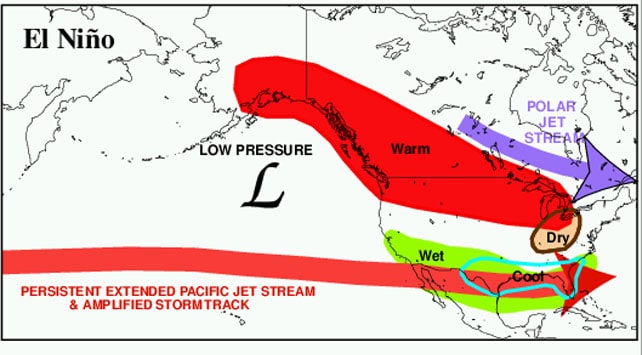

Among the knock-on effects of El Niño is a more persistent southern jet-stream over the US, which is laden with more moisture than normal – and the result is wetter weather over the southern states.

This is not a guaranteed effect. After all, we’re talking about the weather, not a machine. But the consensus is that the stronger El Niño is, the more likely it is to have this “typical” impact.

As you’ll see from the graphic, above, from America’s Climate Prediction Centre, most of this increased storminess passes below the main ski areas of the US and Canada. But not all. The southern Rockies (southern Colorado and New Mexico) are in the firing line, and California too – and California in particular can see big increases in snowfall in El Niño years.

Two of the strongest recent El Niños were in 1982-3 and 1997-8. According to bestsnow.net, the gorgeous, steep and rootsy resort of Kirkwood had 788 inches (20m) of snow in 1982-3, and 588 inches (15m) in 1997-8 – compared with its average of 476 inches (12.1m).

It’s worth pointing out at this stage that California can also see spectacular snowfall when a powerful El Niño is not a factor. For example, at Mammoth Mountain 2005-6 was a year of heavy snow, and this was not an El Niño year. Meanwhile, Kirkwood had a spectacular season for snow in 2010-11, and that was a La Nina winter, the flipside of El Niño, which is supposed to produce drier-than-average winters, not wetter ones.

You also need to bear in mind that not every “strong” El Niño produces heavy snow. 1972-3 also saw quite a powerful phenomenon (though not as powerful as 1982-3 and 1997-8), and it produced below average snowfall at Mammoth Mountain.

As I said, heavy snow is not guaranteed. But the chances of a wet winter in California (with extra snow in the mountains) are increased. And after the recent run of disappointing seasons in the Californian resorts, the onset of the phenomenon has got the local skiers whipped up into a frenzy.

Should you pack your bags and head west to join them? If you’re a powder-munching, ski-anywhere, off-piste addict, then yes, at the very least it should be a consideration. But you have to promise yourself you won’t be disappointed if you’re not up to your eyeballs in powder when you get there – because there are two significant caveats.

1. No two El Niños are ever the same

El Niños aren’t the only complicating factor. Other climate anomalies – such as the Pacific Decadal Oscilliation – have an effect on the weather too. This time round, there is concern about an area of warm sea water in the north-eastern Pacific. It’s thought by some to have been responsible for the recent droughts in California, and some, such as Lake Tahoe snow guru Bryan Allegretto worry that it may diminish the impact of El Niño in 2015-16.

2. You ski snow, not statistics

Even if all the factors work together in California/southern Colorado’s favour, it won’t be snowing all the time. Yes, the likelihood of fresh powder will be increased. But your entire visit may coincide with a week of sunshine – in the middle of a dry, mild month that bucks the generally snowy trend.

You should also bear in mind that El Niño years tend to be warmer than average too. So go no later than early March; or you could face a slush-fest.

Oh yes, and you might also also want to consider the resorts of Utah. They tend get most of their famous snow from storms which roll inland from California and in the winters of 1982-3 and 1997-8 several reported above-average snowfall. These increases weren’t spectacular, but then when the average is high anyway – Alta averages a whopping 14.22m each winter – then that could mean a lot of snow.

Are there any areas I should avoid?

Not all ski resorts are likely to benefit from El Niño. As you’ll see from NOAA’s graphic, above, the other rule of thumb about the phenomenon is that it produces warmer-than-average winters over the Pacific Northwest and western Canada.

This is only a broad outline. As David Phillips, Senior Climatologist at Environment Canada explained to Welove2ski last week, the picture is more complex than that, even for strong El Nino events (he calls them “Super El Ninos”).

First of all, he considered Fernie and Golden (near Kicking Horse), both inland in eastern British Columbia, in the Rocky Mountains. “At both stations El Niño often means milder temperatures and less snow,” he said. “For example, in six Super El Nino events since 1950, five winters had milder temperatures (one colder), and five less snow (one more snow) and 2 more rain (4 less rain). So no guarantee; but the dice are loaded to give you milder temperatures, and less snow and less rain in the interior (winters defined from November to March inclusive).”

Closer to the Pacific, the impact of El Niño depends on elevation. Cypress Mountain near Vancouver tends to get milder and less snowy winters. Whistler is different, thanks to its altitude.

“In effect there is no discernable pattern [in Whistler],” says Phillips. “If anything El Nino causes more snowfall for no particular reason…might be the Pineapple Express storms that bring mild rains to the west coast but snow at Whistler because it is elevated.” Anyone who remembers the impact of a moderate El Nino on the Winter Olympics of 2010 will recognize this effect. There was rain down at the base village in Whistler, but plenty of snow higher up (although it is worth pointing out that, in any winter, you can get rain in the Whistler village while it’s puking snow higher up). Meanwhile at Cypress Mountain, they had to bring in extra snow in trucks.

As for whether or not this El Niño will be affected by the area of warm water in the north-eastern Pacific, Phillips freely admits he has no idea.

“Climatologists like to think that the past is a guide to the future. In this case there is no past. Another wrinkle is the disappearance of the Arctic ice. This is uncharted ground. These are very exciting times for guys like myself but I wouldn’t bet more than a loonie (CAN $) on any forecast coming up.”

And what about Europe?

Once they get round this side of the planet, the knock-on effects of El Niño are mixed with so many other factors, and there are so many variables to consider, that no-one has come up with a convincing model for their effect. One BBC blog in 2014 suggested that “colder, drier conditions in Northern Europe” could be the effect of an El Niño. Then in May 2015, a Met Office blogger said “The increase in risk of a colder winter this year from the developing El Niño is currently considered small”. No clear analysis has emerged so far. So if you want El Niño to have an impact on your skiing, your best chance is to head to the western USA.

Add Comment